Out of all my chronic illnesses and conditions (and there are a lot), Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome is probably one of my least talked about, but also one of my most bothersome. It’s one that causes me the most problems in a lot of ways, but no one understands it, so I never really talk about it. To be completely honest, I’ve been embarrassed by it, because people just assume you’re lazy and always sleeping. The truth is though, a lot of the time I’m sleeping the same amount of time as anyone else, the hours are just different. What is Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome? DSPS is a disorder that is not talked about much, if at all, and it is more common than you’d think. In fact, my boyfriend of a year & a half most definitely has it as well, and what are the chances of that? Well, not unheard of, as it turns out.

What is Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome?

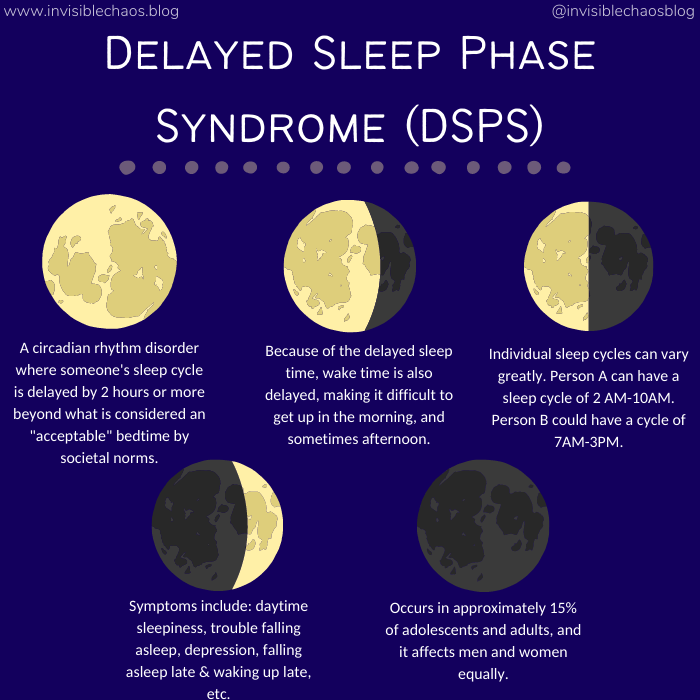

Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome, or DSPS for short, is also known by two other names– Delayed Sleep Phase Disorder (DSPD) and Delayed Sleep-Wake Phase Disorder (DSWPD). DSPS is a circadian rhythm disorder, sometimes referred to as a body clock disorder, where your sleep cycle is delayed by two hours or more beyond what is considered an “acceptable” bedtime by societal norms. Because of the delayed sleep time, the wake time is also delayed, making it difficult to get up in the morning, or whatever time the person needs to for work, school, or whatever commitments they may have.

The American Sleep Association states that when DSPS starts to interfere with life and daily routines, it’s then classified as Delayed Sleep Phase Disorder (DSPD). I don’t see that mentioned elsewhere though, as every other article and journal I read just uses each of the terms interchangeably, saying they’re one in the same. DSPS needs so much more awareness and research, so I’m not surprised. Regardless, it can absolutely cause distress and lead to sleep deprivation from trying to maintain as normal of a schedule as possible.

There are two types of DSPS, both characterized by melatonin. Melatonin is a natural hormone that the brain produces in response to darkness. This hormone helps with the timing of your circadian rhythm (which is your 24-hour internal clock) and with sleep. Being exposed to light at night can block melatonin production.

The first type of DSPS is Circadian Aligned DSPS, where melatonin onset occurs less than three hours before sleep onset. The second type is Circadian Misaligned DSPS, where melatonin onset occurs more than three hours before bedtime, or melatonin doesn’t occur until after sleep onset.

Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome is definitely under-diagnosed, mostly because most people haven’t heard of it. Outside of sleep doctors, I haven’t met one doctor who has been familiar with it. It is common though, occurring in approximately 15 percent of adolescents and adults, and it affects men and women equally.

The times those with DSPS go to sleep can vary greatly, and every person is different. Person A might typically go to bed at 2 AM and wake up at 10 AM. In the grand scheme of things, it’s not too bad, but it can still interfere with everyday life, especially if their job starts at 9AM. Person B might have a sleep schedule of 4 AM and wake up at 12 PM. Person C might have a sleep schedule of 8 AM and wake up at 4 PM. It can go on from there, but as you can see, each person’s schedule can be quite different.

Depending on our sleep cycle, our circadian rhythms can end up being reversed. In seasons like winter where there are not many hours of sun, it can be a severely depressing thing to have because you’re not experiencing much sun, if any at all. In my case, my DSPS combined with my Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) can be quite the depressing combination, and living in the Northeast doesn’t help matters because it gets dark at 4:30 PM in the winter months.

Everyone has that friend who’s a night owl– the one who has more energy at night than they do in the morning, or even during the day. I’ve been that person for as long as I can remember, certainly for more than 20 years at this point. I was spending the late night hours online as a teenager, chatting with friends from all over the world until the wee hours of the morning. In my 20s, I worked as a waitress, knowing I did better at night, but not knowing why.

All night owls don’t have DSPS though, and it’s important to understand that. Some people are choosing to stay up late, whereas someone with DSPS is staying up late because their body clock is delayed. It’s not a choice.

According to the American Sleep Association though, people who are socially active and “night owls” are at a high rate of getting or already having this disorder.

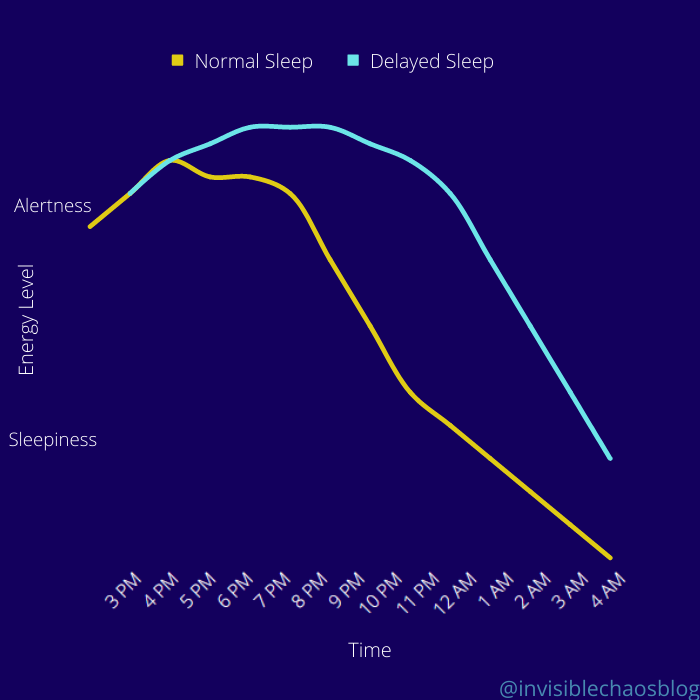

This does not use actual data, this is just an example of the energy levels between “Normal” and “Delayed”.

My Experience with Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome

My own sleep times vary greatly, depending on my fatigue level that day and my insomnia. Regardless of my fatigue though, I’ve always been more of a “night owl”.

I always had trouble getting up for school and later for work. I made it through, but I was always more groggy than the average person was, and I always thought it was just me. Waking up was never easy for me, especially in the morning, it always just felt unnatural to me.

I wasn’t diagnosed with DSPS until a few years ago. I first heard about it in a POTS support group on Facebook, and it blew my mind when I saw someone else mention they had this same problem. Not only did they have this same problem, there was a name for it! I was shocked, and I immediately started to research it to find out more about it. The more I read, the more I realized this was absolutely what I had, no doubt in my mind. I made an appointment with a sleep doctor and he diagnosed me immediately, without me even mentioning it to him.

Unfortunately, as with everything else I have, there’s no cure for DSPS, and treatment often doesn’t work well. The doctor told me that it wasn’t likely I’d ever be on a “normal” schedule though, as it would be the same as forcing someone on a “normal” schedule to be on a sleep schedule that goes against their internal clock.

My DSPS is pretty severe– my natural internal clock changes every couple of years, and it keeps getting later as I get older. For a time, my natural wake time was 1 PM, then 2 PM, then 3 PM. Now it’s between 4 PM and 5 PM. That doesn’t mean every day I’m waking up at these times, but it is happening a lot, as my body feels it’s natural. My schedule is so inconsistent, because falling asleep is so hard for me. I’ve had bad insomnia for decades, and it just adds to the trouble.

Very often, when I try to go to sleep at a “normal” time, my body thinks it’s a nap, and wakes up me up after a couple of hours. So I’ll go to sleep at 11 PM, then wake up at 1 AM thinking “Nice nap, now what?” And that’s it, I’m done for the night. It doesn’t matter if I had a full day of activities and woke up early that morning.

It gets even more complicated when you have other chronic illnesses in addition to DSPS (which is not uncommon, as it can be triggered by an illness), including Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME).

Because of my CFS/ME, it’s very hard for me to go an entire day without a nap. For some odd reason, I don’t need a nap when I’m waking up later in the day (maybe because my body feels like this is the natural time for me), but I very often need a nap when I’m waking up early in the day, even after a full night of sleep. I don’t really understand it either, but it’s just the way my body is.

Now you can maybe start to understand why I’ve been so ashamed of it– waking up at 5PM is an extreme. Some people with DSPS wake up at 10 AM, and they can still function normally. No matter how hard I try, it’s so hard for me to function normally, because I just can’t sleep at normal times very often, as hard as I try. I may go a few days with “normal” times (waking up at noon, for example– it’s very rare I’ll wake up at 7 or 8 AM, although it can happen, but I’ll need at least 1 nap during the day), but my schedule never wants to stay that way.

It always reverts back to what my body feels is natural, and that’s going to sleep later (or earlier, depending how you look at it), and waking up late in the day, or early in the evening (again, depending how you look at it).

It’s said that having DSPS is like living with jet lag, and I think that’s a pretty accurate description. It does feel like we’re living with jet lag– completely misaligned with the normal world.

I often wonder if I lived in another part of the world (where it’s 12 hours ahead my current time zone), if I’d be able to adjust better. I know the real answer though — of course I wouldn’t. My sleep schedule would just readjust to what it thinks is a normal sleep time, and I’d just be in another country with the same problem.

Some might be thinking “well just take a sleep aid”. It’s not that simple. I’ve taken multiple different sleep aids at this point, and none of them work on me the way they would work on a person with a regular sleep schedule. Ambien was like taking water, Trazadone did nothing, and a bunch of others I can’t remember the names of did nothing as well.

There was only sleep aid that I tried over the years that did anything, and I’ll never take it again. I can’t remember which medication it was, but it left me on my bed, wide awake and paralyzed. It wasn’t sleep paralysis, because I’ve had that from another sleep aid and I know that horrifying experience too well to mistake it. With this, I was still wide awake. I also couldn’t move my limbs (both arms and legs), but my breathing became depleted through my nose. It was the scariest experience, because I could barely breathe. I thought I was going to have to scream out for help to go to the hospital, and then, within those few minutes, I somehow fell asleep. I woke up the next day thinking “never again”. I told my doctor about it, and she told me it was not an unusual response. No thank you.

Our bodies just don’t seem to respond to medications. My sleep doctor told me the reason melatonin is suggested (and different) is because it trains our bodies into thinking that whatever time we take it should be the normal bed time.

I’ve been taking melatonin every night for a year and a half though, and it has done nothing. I still take it though, hopeful that it’s giving me some unseen benefit I don’t know about.

Quick facts on DSPS.

Symptoms of DSPS

Symptoms can vary greatly, based on person. But some include:

- Daytime sleepiness.

- Trouble falling asleep.

- Falling asleep late & waking up late.

- Difficulty concentrating.

- Difficulty remembering things.

- Difficulty waking up.

- Depression (nearly 50% of those with DSPS suffer from it).

- Other behavioral changes.

- Dependency on caffeine, sedatives, and/or alcohol.

- Needing to nap during the day.

- Excessive sleeping on the weekends to make up for less sleep during the week.

Causes of DSPS

- Genetic component — those with family history of DSPS are 3 times more likely to develop DSPS.

- Chronic insomnia.

- Psychological disorders.

- Neurological disorders.

- Brain damage from an injury, stroke, or a degenerative disease.

- Changes after puberty.

- Poor sleeping habits.

- Autonomic dysfunction aka Dysautonomia — there are little-to-no studies done on this, but we do know that circadian rhythm is an autonomic function. The autonomic nervous system have functions that happen in our body involuntarily, without us thinking about it, or controlling it (this can also include blood pressure, pupil dilation, digestion, heart rate, and more). Therefore, it stands to reason that those with dysautonomia (I have POTS, for example, which is a form of dysautonomia) are susceptible to developing DSPS. We already know those with dysautonomia can have sleep disturbances, but this is just one diagnosis that is not talked about in connection with dysautonomia, and someone needs to do a research study on the connection.

- Other chronic conditions and illnesses.

Treatment for DSPS

As I mentioned above, there is no cure for DSPS. There are some people who either grow out of it, or have been able to get back to a “normal” schedule, however, there is typically a high level of resistance towards treatment, and most people have to just learn to adjust accordingly.

If you believe you have a sleep disorder, including DSPS, seeing a sleep doctor is always recommended.

- Bright light therapy — exposure to bright light at early morning hours shortly after waking up. Can be done with natural light or with a light box. In addition, avoiding bright outdoor lights during the evening hours.

- Taking melatonin supplements.

- Advancing your internal clock — each doctor might suggest a different schedule, but one method is going to bed 15 minutes earlier each night (or day, depending when your usual time to fall asleep is.) You’ll also wake up a little earlier each day.

- *Delaying your internal clock (also known as chronotherapy) — involves delaying your sleep schedule by 1 to 2.5 hours every 6 days. This is done until a normal sleep schedule is reached.

- Improving sleep hygiene — in addition to following a normal sleep schedule, doctors suggest avoiding the following before sleep: electronics (phone, TV, computer, etc.), caffeine, tobacco, alcohol, and rigorous exercise.

*What’s tricky, and also dangerous, about some of the treatments is it is possible that DSPS can turn into a more serious circadian rhythm disorder called Non-24 Sleep-Wake Disorder (N24). The treatment that cause DSPS to develop into Non-24 is chronotherapy, and because of this, some doctors won’t even recommend trying this method. I’ve read of quite a few cases in the DSPS support group on Facebook about people who have developed N24 after trying the chronotherapy method.

Non-24 is a more serious circadian rhythm disorder that affects up to 70% of all blind people. You don’t need to be blind in order to develop N24, however. The average person has a 24-hour schedule. A person with N24 do not have the internal clocks that reset and stay balanced within a 24-hour schedule. According to the ASA, those with Non-24 have longer loops, typically resulting in 25 or 26-hour cycles, although more dramatic cases have been documented, but they are more rare.

Because of the possibility of DSPS possibly developing into Non-24, caution is recommended for treatments, especially chronotherapy.

What is “Normal” Anyway?

The need to adjust your schedule may feel like a necessity, and personally I do feel like I need to try harder and work on it more. I want to be a day person.

Those in the DSPS community often call people who are on a normal schedule “day walkers”, and as much as I want to be one, I can’t force it either. I don’t expect to be on a completely normal schedule anytime soon, but adjusting it so I can at least live a fuller life would be ideal. Waking up when everything is closing is not convenient, that’s for sure.

For those that can’t change their sleep schedule (and there are many), we are perfect candidates for working at night, or at the very least later shifts that no one else wants. At my last job, I worked 10 AM until 6 PM, and that extra hour made a huge difference to me, because I needed that extra hour of sleep since I have such trouble sleeping early.

Years ago, before I was diagnosed, I told one of my old doctor’s about my sleep schedule, and she told me that no one who sleeps during the day and is up at night (even people who work night shifts) get quality sleep during the day. I don’t know if there’s any truth in that (I personally think there’s probably not), but I know my sleep always feels more restorative when I sleep what my body feels is normal. And from what I’ve read about DSPS, people who sleep when their body wants them to do get restorative sleep, as long as they’re sleeping long enough.

I don’t often get much restorative sleep though, because of my other conditions, but when I do, it’s rarely when I’m sleeping at what is considered a “normal” time, like from midnight to 8 AM.

The most important thing you can do is making sure you’re getting enough sleep, regardless of what time you’re sleeping.